ADVISOR: Jon Sanford

RESPONSIBILITIES: Prior research, user research, storyboarding, analysis, ideation, prototyping, user testing

PRIMARY RESEARCH: LITERATURE REVIEW

I researched literature and prior art in order to frame the importance and effect of different characteristics of play that relate to communication, and factors that influence the efficacy of those characteristics. I started my research with the assumption that the environment (e.g. playground equipment) is an essential tool to encourage play.

Key Findings:

My assumption about the play environment was confirmed

Plenty of research exists on teaching communication through play with games and toys, and on interactive environments that encourage play for the purpose of physical and cognitive growth

There is a gap between the two, however, where little work has been done using an interactive environment to specifically evoke speech between children during play

Role-play is a common vehicle for jump-starting communication, since it provides a familiar script to follow, while allowing a child to step outside of themselves and let go of social anxieties

PRIMARY RESEARCH: EXPERT INTERVIEWS

I partnered with the Atlanta Speech School in order to carry out my research. I conducted interviews with the school’s teachers, speech-language pathologists, learning disability specialists, and occupational therapists to ask questions I derived from the literature review insights.

Key Findings:

Non-specific environments are best for driving imaginative play, but can’t be so abstract that children don’t know how to interact with it

In order to accommodate a wide spectrum of physical and mental abilities, interactions with the environment should be multi-sensory

As physical development sets the foundations for cognitive development, it’s important to intrinsically motivate movement

During inclement weather or extreme temperatures, children at the school were limited to playing in the gymnasium and didn’t have access to the flexible setting for the sort of equipment that encourages movement

DESIGN CRITERIA

The topics from the primary research turned into the design criteria for the project.

DEFINING THE SCOPE

The project was limited to play on the playground (as opposed to at home, at after-school clubs, etc.) so it wouldn’t be too open-ended. The playground also served as the ideal testing grounds because of the high chance for spontaneous interactions.

The project focused on children between the ages of three and eight years old, as this range encompasses the most crucial developmental stages of communication.

SECONDARY RESEARCH: NATURALISTIC OBSERVATION

I received permission from the Atlanta Speech School and from parents to observe children during recess. The purposes were to further inform the design, provide control group data for comparison later on, and refine testing measures. I came up with a behavioral map and accompanying characteristic matrix to help record my observations.

Key Finding:

While the design of the playground equipment is indeed useful for inviting communication, it’s more important how the child perceives the environment.

INSPIRATION

I had initially started brainstorming ideas for a playground structure, but turned towards augmenting the playground experience instead after the initial observation session. I took inspiration from Andersen’s ‘ensemble’, which featured a collection of interactive garments and props to be used for dress-up games by children. The children were gathered at a workshop and were free to explore the affordances of the wearables as interfaces. However, the concentration of the study was not on generating communication, and children played independently for the most part.

IDEATION

I started sketching ideas for wearables to provide an on-body interactive environment that would respond with a wide range of feedback to children’s movement or manipulations. A wearable fulfilled all of my design criteria:

Nonspecific - A single prop could be used for multiple roles

Flexible setting - A wearable would be portable enough to use indoors or outdoors

Movement - Sensor technology could be added to encourage movement

Multi-sensory - Multi-modal feedback could be added in the form of lights, sounds, and vibration

Role-play - And of course, the wearable would promote role-play

EXPERT FEEDBACK

I showed my initial concepts to the experts at the Speech School to get their thoughts on the designs.

Key Findings:

General items preferred (things like skirts, hats, and capes, over things like wands, tails, and wings)

Concern for children with sensory integration issues - vibration is a disorienting stimulus, while weight on the body is calming

REFINEMENT

I narrowed down the concepts into a cape for several reasons:

Solved the sensory integration issue

One of the best forms to afford visibility to both the wearer and other people

Most flexible use; genderless, didn’t require fitting considerations like a shoe or glove would have, easy to put on and take off

INTERACTION STORYBOARD

The concept centered around an accelerometer that set off lights and sounds in response to movement. Vibration sensors were also added to the design to generate more varied actions with the cape, but since the main goal of the project was to provide children opportunities to talk to each other, it needed something else to facilitate those interactions. I wanted to have children work together to trigger a special effect as a reward from their interaction.

The refined concept allowed for a child to play with the garment by him or herself, but also have the chance to interact with a peer to activate even more stimulating feedback. Expert feedback said extra sounds or light colors were enough of a reward. I decided on adding matching shapes on the capes based on matching games young children play.

BLANK CAPE OBSERVATION

As part of my prototyping phase, I made a set of plain capes without electronics to introduce to the playground. I found that the capes needed to be heavier so they wouldn’t fly up into the face, and adjusted some minor fitting issues.

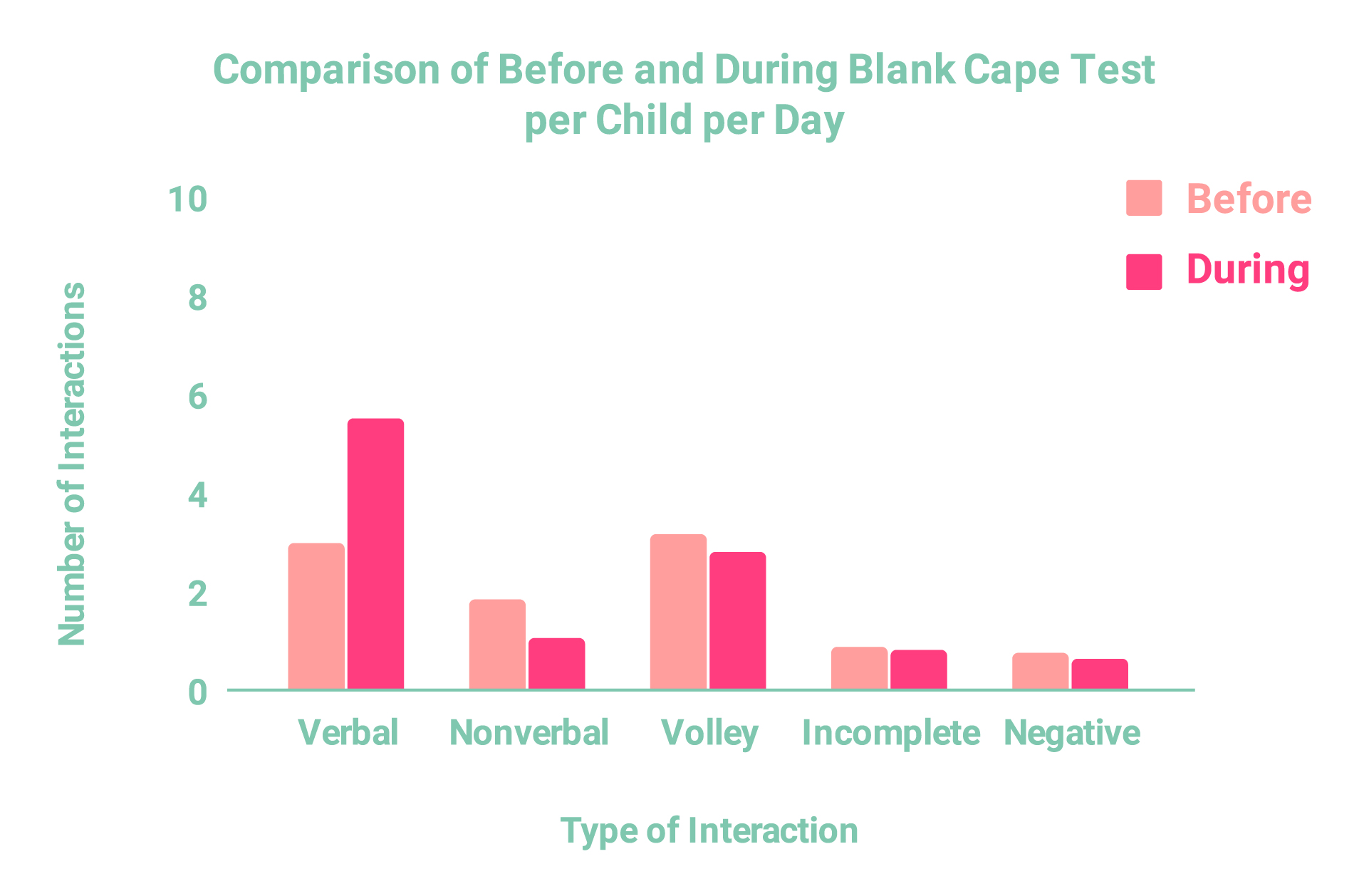

This observation session also set the baseline for final user testing. Below, you can see a variety of colors including the ones indicating incomplete and negative behaviors, and very little volley.

Sample Behavioral Map From Blank Cape Session

PROTOTYPING: DESKTOP MODEL

The desktop model allowed for troubleshooting the code and hardware before having to worry about the more finicky connections on the cape.

PROTOTYPING: FULL BUILD

I built a set of three fully functional interactive capes. Each one was programmed to have unique colors and sounds in response to the same activations.

USER TESTING

Testing was conducted using the same methodology as the initial observation and the blank cape session.

The same 9 subjects were observed during both the blank cape session and the final testing session.

Much more volley was observed during testing, as seen in the example behavioral map below.

DATA ANALYSIS

The data indicates the testing was successful. It shows an overall increase in the number of interactions observed.

It also showed an increase in desirable behavior, and a decrease in undesirable behavior:

Desirable behavior:

113% increase in verbal

95% increase in nonverbal

181% increase in volley

Undesirable behavior:

33% decrease in incomplete

7% decrease in negative

One thing to note was that the nature of negative interactions changed because of sharing problems with the cape.

DISCUSSION

The capes created more opportunities for communication, even when the kids weren’t previously interacting with each other. Children would ask for a specific cape color or for someone to help them put it on.

Cape-wearers tended to gravitate towards each other. Kids would disperse upon first receiving the capes and then start playing with each other. Their interactions included role-play and exploratory play.

Younger (3-5) and older (6-8) children played differently. Younger children were more organic with their play while older children made up rules about the capes.

Children did some unexpected things with the capes.

Kids never discovered the special effect activation on their own.

CONCLUSION

A weakness of the methodology was that that children were only observed over two days each for the initial observation and testing phases. The data can’t conclude how much of the change is from the novelty factor, but the study does indicate that bringing something interactive to the playground can increase desirable behaviors and decrease undesirable ones.

FUTURE STEPS

Subjects should be observed over a much longer period of time to draw better conclusions from the data.

More study is needed to refine the collaborative interaction trigger indicator, and allow for evolving novelty within the design.